OUT NOW “TRITTICO” NEW RELEASE FROM CONCERTO CLASSICS

LISTEN ON ALL STREAMING PLATFORMS: https://bfan.link/trittico-2

.

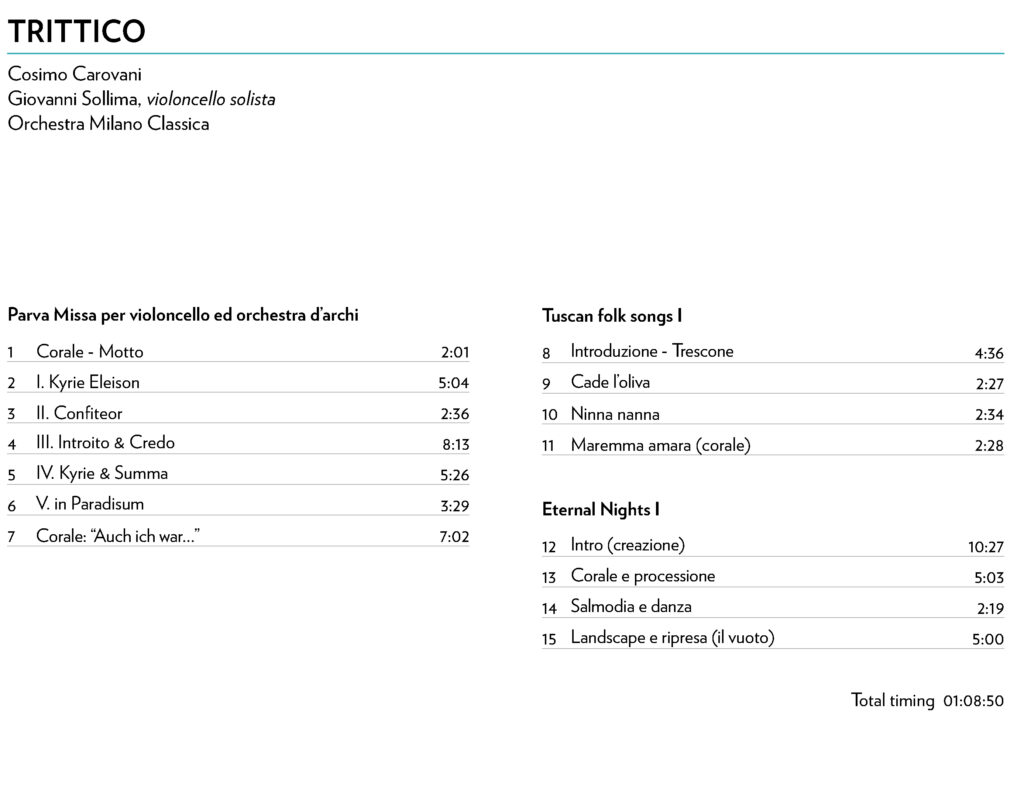

Cosimo Carovani

Giovanni Sollima

Orchestra Milano Classica

.

The three parts merge in the concepts of roots, unconscious and religiosity,

transforming the TRITTICO into a profound and engaging musical experience.

.

This album offers an immersion into the musical world of Cosimo Carovani, an eclectic cellist and composer who, through his collaboration with Giovanni Sollima and Orchestra Milano Classica, presents this project revealing the different souls of his talent. With the three works Parva Missa - Tuscan folk songs I - Ethernal night I, this "Triptych" shows us a deep exploration of the musical sensibility of the composer, who is completely immersed in the search and experimentation of the new in this our present. The decision to write for a string orchestra, conceived as a large quartet, is the result of the fusion of the experiences of Carovani, cellist also of the famous Quartetto Indaco (the first quartet in Italian history to win the gold medal at the Osaka International Chamber Music Competition).

Written during the pandemic, the Parva Missa for cello and string orchestra (dedicated to Giovanni Sollima) embodies in music, as the composer himself states, those "tremendous moments of loneliness while the world outside the walls suffered from fear and uncertainty." In the Chorale, Opening Motto, the first orchestral viola appears with psalmody (a recurring four-note C#-A-E-B motto) as the officiant of a rite, a role which is later invariably taken by the solo cello: the orchestra responds to it as a chorus of worshippers. In this incipit there is a strange, enigmatic serenity, perhaps the breath of nature regaining possession of the world and leading us to question the meaning of existence. More dramatic is the Kyrie Eleison, a reflection of a contemporary Sehnsucht in which the cello's voice ("enchanted, full-voiced, dreamy") shifts from dreamy sweetness to expressionist violence, while the orchestra often mirrors a celestial dust, divine Nature interrogated by the soloist's psalmodic entreaties. After a intermission, repeated notes from the cello ("sighing") prelude a resurgence of drama (Confiteor), which becomes tragedy, on the inexorable "stomp" scansion (the orchestra stamps its feet on the ground): almost as fate knocking at the door. Fiery bow turns by the soloist introduce a grand climax, leading "up to the noise," in an atmosphere of despair. On the edge of the abyss, a sudden silence precedes the Introit and Credo, in which the soloist plays and sings at the same time: the human voice becomes a gesture to recreate the world. Amid doubt and torment, the crescendos this time seem to embody a desire for reconstruction. The cello engages in a kind of struggle with negative thoughts expressed by some ominous phrases, until a new climax is reached, ffff. Kyrie and Summa present us with a rhapsodic soloist, seeking freedom, finally finding it in In Paradisum.But the regained serenity, far from naïve, leaves behind a nostalgic wake, expressed with intimate and poignant pathos in the concluding chorale "Auch ich war": a vein of fatalistic sweetness tinges the last notes with Wehmut, thanks to a dialogue between cellos rising to the treble, like stretching towards the Supreme Good.

With Tuscan Folk Songs I we travel to stronger hues: the folk universe of traditional Tuscan songs becomes a starting point for radical coloristic experimentation. The Introduction, a Preghiera su Maremma amara, a song about the alternative between dying of starvation and dying of malaria, "slow, smoky, speaking," evokes the whispers of nature; the Trescone, a dance of medieval origin, opens instead with a theme swaggeringly expounded, homophonically, by the tutti strings, to which the highest section responds on distorted harmonies. As in Casella's Italia or Richard Strauss's Aus Italien, the composer exaggerates folklore to the point of making unheimlich (perturbing, unfamiliar) what was originally heimlich. The interplay of harmonic sounds, even in visionary glissandos, and register contrasts deepens in "Cade l'oliva," another folk song, metamorphosed into a slow waltz. The estrangement deepens with Lullaby (Lullaby of the Seven Winds), far from merely tranquil, until bitter Maremma explodes again in the form of the concluding chorale, pompously festive and sacred at the same time, with the strings treated at times as a meta-organ. On the whole, in addition to historical twentieth-century ethnomusicological composers such as Bartók, thoughts turn to the Berio of the Folksongs: while dealing with geographically homogeneous material, one notices in Carovani a multicultural perspective, musically drawing on disparate sound and linguistic universes.

Much more confrontational, on the other hand, is the ancestral universe of Eternal Nights, almost a dialogue-fight in which the macrocosm of the Universe and the microcosm of the unfathomable human soul mirror and question each other. The opening Adagissimo evokes creation ("may eternity be felt"): the pianissimo is broken, however, by a violent fortissimo, like a noise, the first in a series of interruptions of a kind of primal peace. The string group often becomes an "other" instrument, a kind of organum that can evoke a vox cœlestis or menacing monsters. In four movements, the composition moves from the solemnity of a Chorale and Procession to a more secular vein in the Dance that follows the Psalmody, incorporating into the material numerous twentieth-century references, both from the world of songwriting and from Stravinsky's world (references to rhythmic patterns from the Sacre du printemps are evident). In the final part (Landscape and reprise), the quatrains of all the muted instruments seem to evoke a "noise of stars" interrupted by sudden lashings, before the mystery of Being is once again celebrated, at the threshold of silence.

Luca Ciammarughi

.